Everywhere you look online, the claim that the American shopping mall is dead is treated as fact. But drive down to Costa Mesa, California, and you’ll find a mall that quietly disproves it. South Coast Plaza, which opened in 1967, has remained not only open, but among the most profitable malls in the country, generating close to two billion dollars in annual sales.

So why has this mall endured while so many of its peers have declined, hollowed out, or disappeared?

The easy answer is its collection of luxury tenants. But that explanation is incomplete. South Costa Plaza survives because it was conceived, and continually refined, as a designed environment. And for nearly sixty years, the same family has held it to that standard. The Segerstorm family, who built the mall and still owns it today, has treated reinvention and design quality not as decoration, but as strategy.

And it’s worth stressing what South Coast Plaza is up against. This isn’t a lone mall hanging on in a retail desert. It’s operating in one of the most competitive shopping landscapes in the country, in a region dense with major centers, many of them high-end, many of them constantly renovating, many of them built to siphon the exact customers South Coast Plaza relies on. In a place where shoppers have options, South Coast Plaza has managed to stay on top.

From Lima Beans to Shopping Destination

It all started with a lima bean farm. The land that’s now South Coast Plaza has been in the Segerstorm family since 1898, when they arrived in the United States from Sweden. What began as forty acres grew into roughly 2,500 acres of agricultural land, with lima beans as the signature crop.

But land has a way of changing value when a region grows up around it. As Orange County surged into its postwar boom, the Segerstorms diversified beyond agriculture and into real estate, positioning the family to shape what their land would become rather than simply selling it off.

That shift set the stage for Henry Segerstorm, who came of age at the exact moment Orange County was accelerating outward. In the early 1960s, Sears approached the Segerstorms with a proposal: lease the land and let Sears develop a shopping mall through their Hormat Development Company. They pointed to one of their recent projects in nearby Buena Park as evidence of what they could deliver.

Henry Segerstorm visited the mall and left unimpressed. He didn’t doubt that a shopping center would succeed, he doubted that this version of one was worth surrendering control over. But the offer revealed something important: if Sears wanted to build here, it meant the site had all the ingredients for a major center. Segerstorm decided he would build it himself, only better.

Two Visionaries Designing a New City

Despite detractors questioning whether the surrounding population could support a project of this scale, Segerstorm moved forward and began searching for architects, The name that stood above all others was Victor Gruen, the designer who had done more than anyone to define the enclosed American shopping mall.

Gruen believed a shopping mall could become a civic nucleus, a surrogate downtown for communities that had grown without a traditional city center.

Segerstorm shared that ambition and hired Gruen not just to design a mall, but to plan the larger development around it. Gruen outlined his thinking during South Coast Plaza’s planning stage:

“We believe that shopping centers will soon become just ‘centers,’ and will contain multiple urban activities…” – Victor Gruen

The implication wasn’t subtle. South Coast Plaza wasn’t meant to be an island of retail. It was intended to anchor something larger–a district that could function as a hub of activity for a place that didn’t yet have one.

A Mall Designed Like a Town Square

Gruen assigned the design to his partner Rudi Baumfeld, who had worked on Southdale Center and became a key hand in many Gruen malls. The result carried the familiar DNA of the Gruen formula, but with a level of refinement that helped it age better than most.

Sears and the May Company anchored either end. Parking was organized across levels, with a berm that allowed shoppers to enter from the first or second floor, eliminating the perception that the upper floors were secondary. A central air-condition system cooled the interior through Southern California summers.

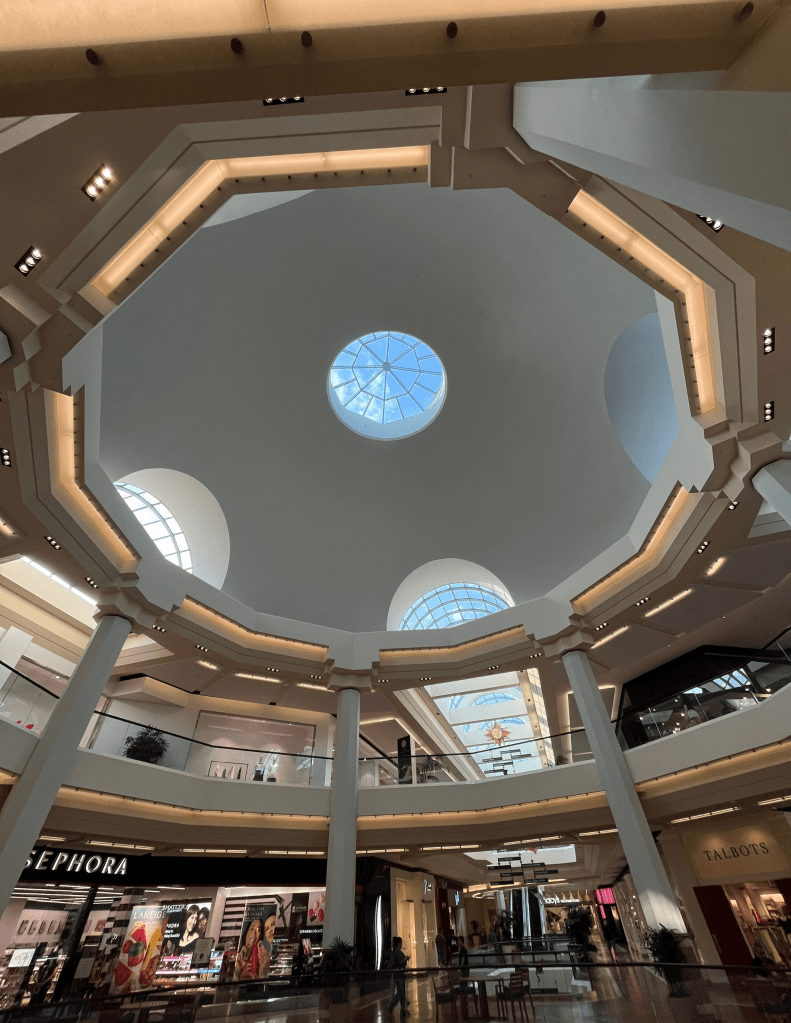

Most importantly, at the heart of the plan was a central court based on the proportions of a Viennese square. Trees and plants brought softness and scale. Skylights pulled daylight into the interior. The effect created a space where people were encouraged to linger.

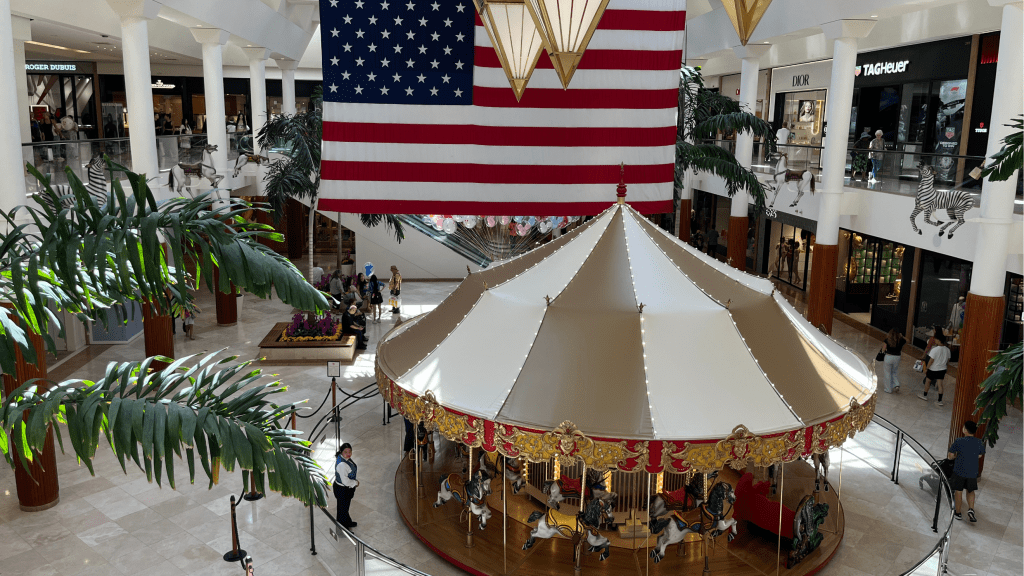

As an added landmark, Gruen included a carousel. It was a small gesture in practical terms, but it mattered in the way it sharpened memory. It introduced movement and sound, turning the court into a meeting place.

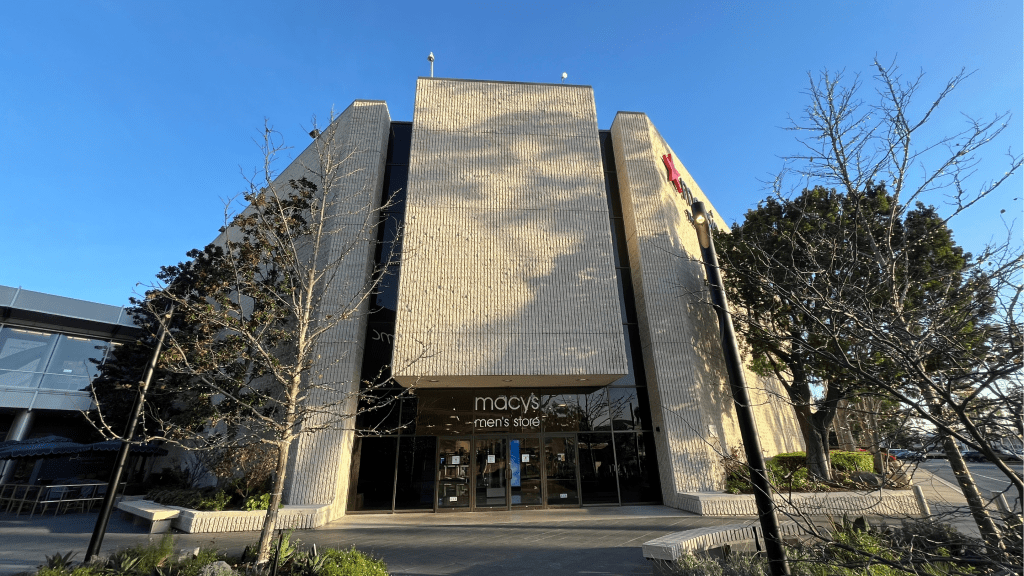

Groundbreaking took place in 1965. Construction used precast, prestressed concrete, the first time such a system had been used in California. The May Company opened first in late 1966, followed by Sears and the rest of the mall in March 1967. Almost immediately, South Coast Plaza proved what Segerstorm suspected all along: not only would it work, it would thrive. Within a year, expansion planning was already underway.

Importantly, expansion was never an afterthought. It had been built into the project’s from the beginning. Gruen anticipated growth, and the structure reflected that flexibility, with portions designed to be removed or extended as future phases came online. That approach allowed South Coast Plaza to do something many malls struggled with later: grow without compromising its core experience.

Expansion, Identity, and a Rare Kind of Continuity

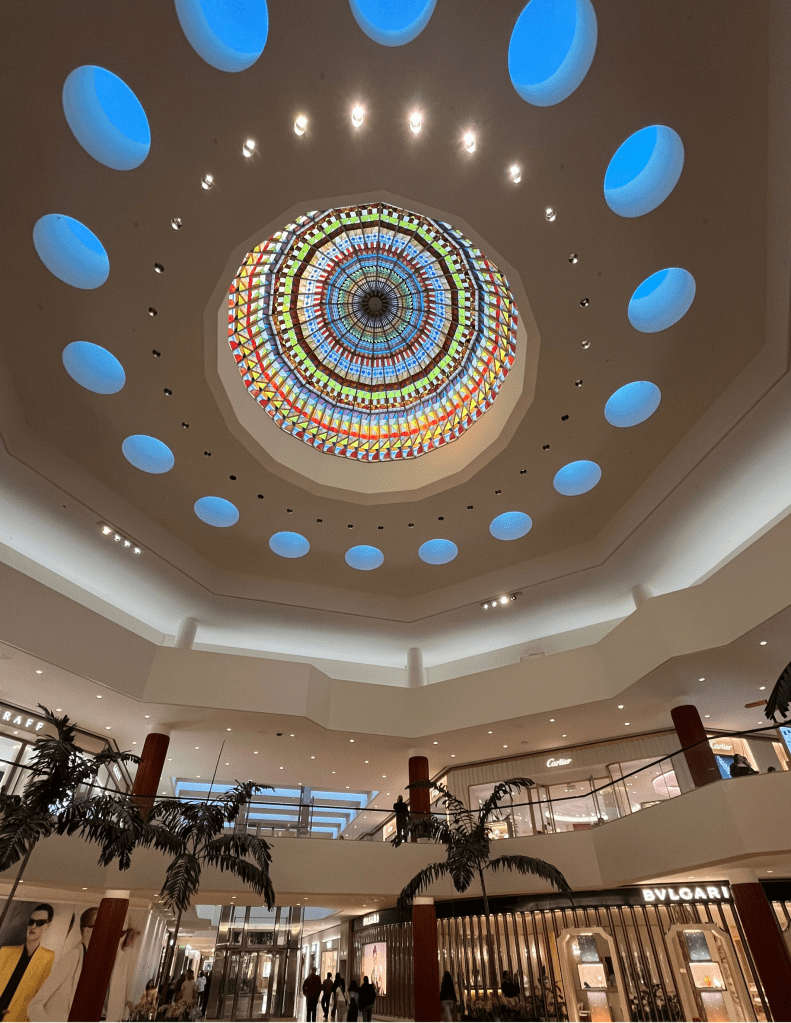

The first major expansion arrived in 1973, extending outward from the original Carousel Court to a new Jewel Court. It introduced a stained-glass dome designed by Marion Sampler, Gruen’s head graphics. The dome became an elevated feature that reinforced the idea that South Coast Plaza was an architectural experience.

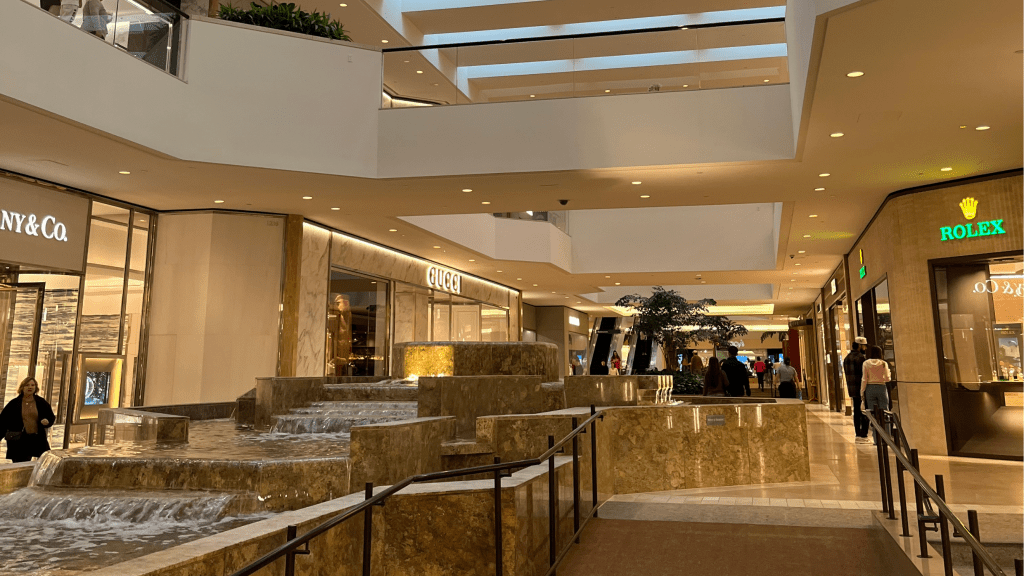

To anchor the expansion, Bullock’s arrived with a store designed by Welton Becket and Associates. The building carried the company’s suburban department story identity, with a pyramidal roofline and brick facade, an architectural shift that signaled how South Coast Plaza could absorb multiple design languages while remaining coherent. The concourse itself introduced sculptural elements, including an angular fountain with water stepping down concrete forms.

By this point, South Coast Plaza had proved itself as a commercial and design success. The architecture was compelling enough that Julius Shulman photographed it–an extraordinary signal, considering malls were rarely treated as serious subjects of architectural documentation.

And yet, even as South Coast Plaza was proving Gruen’s ideas could work under the right conditions, Gruen was growing disillusioned.

Gruen’s Rejection of His Creation

A year after South Coast Plaza opened, Victor Gruen left his firm and returned to Vienna. It wasn’t a quiet retirement. He was frustrated by what the American shopping mall had become.

Gruen had hoped the mall would serve as an organizing civic element for suburbia, creating dense, walkable, mixed-use, and integrated into the life of a community. Instead, he watched his concept get replicated without the parts he considered essential. The mall became retail surrounded by parking, an accelerating for the very sprawl he despised.

In hindsight, that’s what makes South Coast Plaza so unusual. Not because it perfectly fulfilled Gruen’s idealism, but because it preserved more of it then almost anything else built in the same era. South Coast Plaza, and the larger South Coast Metro area that grew around it, remains one of the clearest surviving examples of what Gruen meant when he imagined shopping centers becoming true “centers.”

Frank Gehry and Luxury

South Coast Plaza always carried a broad tenant mix, but over time it developed a second identity: a mall with design credibility. One of the early luxury arrivals was Joseph Magnin, designed by a young Frank Gehry. Gehry had worked for Gruen in the 1950s, and by the late 1960s he was forging a reputation as an architect who could be experimental without sacrificing the commercial viability of the space. The Josephn Magnin store opened in 1968 near Carousel Court, bringing a minimalist edge to the mall’s interior.

Segerstorm took notice. When I. Magnin was developing a store at the mall in the 1970s, Gehry was selected again. The store opened in 1977 with a minimalist white concrete block exterior with entrances placed at the corners rather than the center. Black glass visually operated portions of the facade, allowing the walls to appear slightly disconnected. It was an architectural trick that made the building read less like a retail box and more like a composed object.

Crystal Court and the Postmodern Turn

The late 1980s brought another major expansion, and with it, a visible stylistic shift. A new wing connecting to the Jewel Court developed alongside an expanded Nordstrom, reinforcing the mall’s position in the luxury landscape. But the biggest transformation arrived in 1986, when a new mall complex was built across the street.

Designed by Gruen Associates, Crystal Court expanded South Coast Plaza into a three-story environment that leaned into the warmer tones and historical references of postmodern architecture. Around the same time, renovations to the original mall altered elements of its 1960s character, introducing brass pyramid motifs into the Carousel Court.

In many malls, this era marked the beginning of long-term identity loss. Renovations diluted original character. Expansion felt disconnected. Design decisions increasingly served short-term financial logic.

But at South Coast Plaza, the underlying pattern remained more consistent. Whether the language was modern or postmodern, the center continued to invest in the experience of its spaces. It retained courts. It retained fountains. It retained landmarks. Even as other luxury malls began replacing their interior gathering spaces with kiosks and revenue-generating concessions, South Coast Plaza held onto the elements that made it feel like a place rather than a passage.

The Mall That Became a District

As the mall expanded, so too did the Segerstorm land around it. Reflecting Gruen’s early ambitions, the South Coast Metro area grew into a broader concentration of activity: office buildings, a hotel, cultural venues, public art, and parks woven through the district, and remaining at the center of it all was South Coast Plaza.

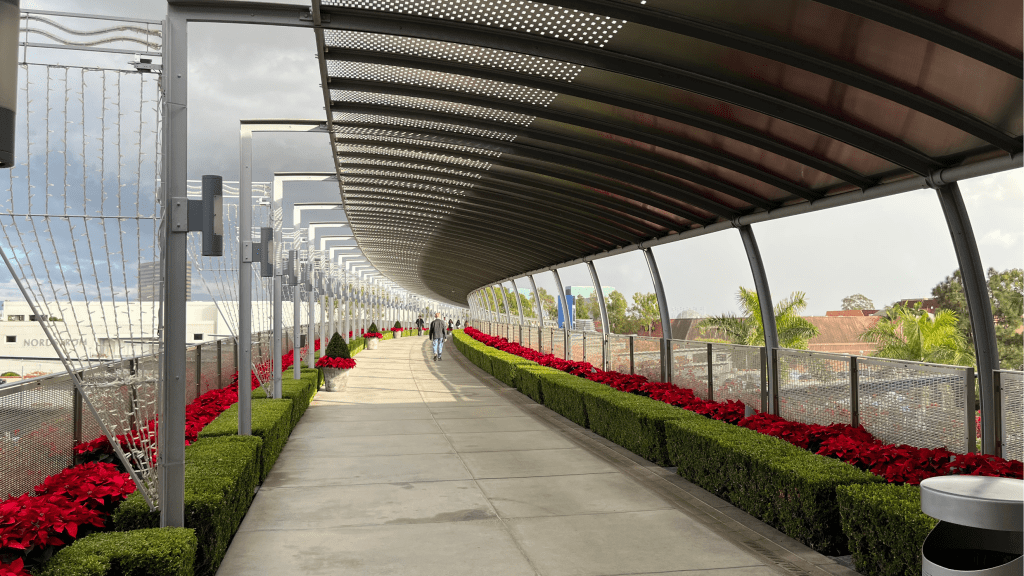

Part of what kept South Coast Plaza at the heart of the region was its ability to connect with the surrounding area. Segerstorm built a pedestrian bridge linking the commercial and cultural facilities with the mall across the street. He also commissioned the landscape architect Kathryn Gustafson to design a bridge and garden to link the original mall with the Crystal Court. The Bridge of Gardens served as a continuation of the larger shopping experience. There was an outdoor café beneath a canopy of lights, gardens, and a vantage point overlooking the surrounding neighborhood.

These bridges were built manifestations of what Segerstorm had been moving toward for decades as something closer to a city center than an isolated building.

South Coast Plaza Today & Why It Still Works

In recent years, South Coast Plaza has continued to hold its grown even as the broader mall ecosystem has weakened. It has stayed current without surrendering the qualities that made it successful in the first place. Part of that is retail gravity, of course. But the deeper reason is architectural stewardship. The Segerstorm family has consistently treated the mall as an ongoing project–one that must evolve, but not at the cost of design integrity.

That’s why the bones of Gruen’s original idea still matter. South Coast Plaza still reads like an interior city, defined by courts, daylight, fountains, planting, and spatial hierarchy. Where many malls stripped their atriums to make room for kiosks and temporary leasing strategies, South Coast Plaza retained its internal landmarks, Its space have been refreshed and updated, but the center continues to invest in the idea that people don’t just come to the mall to shop. They come because it still feels like somewhere worth being.

South Coast Plaza doesn’t disprove the death of the mall simply by existing. It disproves it by demonstrating what happens when a mall is designed well, and is owned by people wiling to keep making it better. In Costa Mesa, the American mall didn’t survive by standing still. It survived by treating design as the product, and reinvention as part of the plan.

Leave a comment