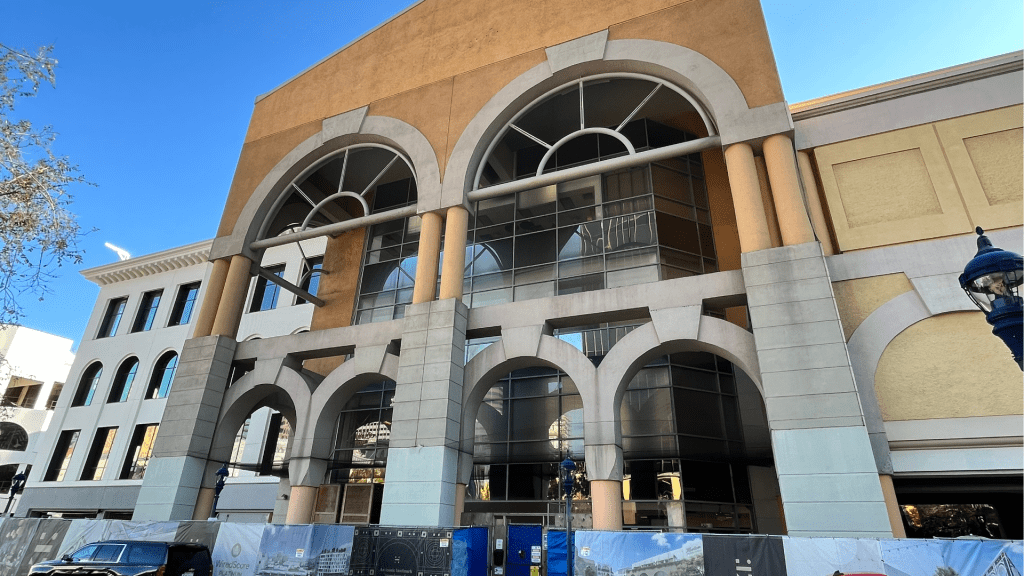

It was May of 2023, and the marine layer began to part as a small group in hardhats gathered beneath the postmodern pediment of the old Macy’s in downtown San Diego. Through the chatter, a man stepped out from behind the construction fence and invited us to glimpse the future of one of San Diego’s most iconic buildings: Horton Plaza.

The Jon Jerde-designed mall had served as a catalyst in revitalizing downtown San Diego in the late 1980s. Its theatrical composition of ramps, terraces, and pastel facades drew visitors back into the city at a time when suburban shopping centers threaten to hollow it out. But architecture alone cannot suspend economic reality indefinitely. By the mid-2010s, its once-charming maze of walkways had grown tiresome for shoppers, tenants began to leave, and the mall effectively closed in 2020 during the pandemic. What remained was a white elephant in the heart of an otherwise thriving downtown.

Some proposals called for demolishing the complex entirely. Preservationists pushed back, arguing for the survival of Jerde’s unmistakable facades. Eventually, a compromise emerged. Stockdale Capital Partner purchased the property with plans to transform the mall into a mixed-use campus of offices, shops, and housing–and attempt to translate the structure into a new economic reality.

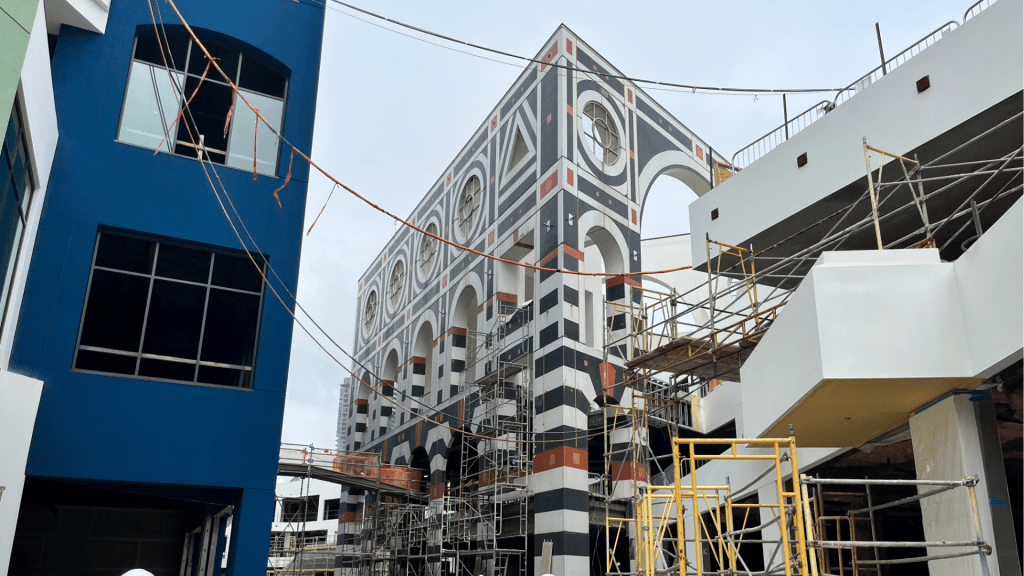

Walking through the abandoned Macy’s and back into the California sun, it seemed they had struck the right balance between preservation and reinvention. The mall’s famed Palazzo Building remained intact, its black-and-white tiled facade still announcing itself with theatrical confidence. Elsewhere, portions of the labyrinthine circulation had been opened, reconnecting the project to the surrounding city.

The enthusiasm was convincing. The physical progress even more so. It was easy to believe the project would be completed by it opening date of 2025.

But here in 2026, the site sits behind construction walls, half finished and foreclosed on. The Campus at Horton remains suspended between its past and its future.

Horton Plaza reveals an uncomfortable truth about adaptive reuse, particularly at the scale of the American shopping mall. These buildings are not empty shells waiting patiently for new purpose. They are highly specialized machines, designed around a single use and a single economic logic. Once that logic fails, the architecture itself becomes extraordinarily difficult to translate.

A Building Designed to Look Inward

The difficulty begins with the mall’s fundamental geometry.

Unlike office buildings, which organize their floors along exterior windows, or warehouses, which prioritize open flexibility, enclosed malls were designed to pull people inward .Their corridors face each other, not the outside world. Their storefronts look into artificial streets, not real ones. Daylight, when it appears at all, is carefully rationed through skylights positioned to dramatize space rather than evenly illuminate it. Everything about the mall’s plan assumes a constant choreography of browsing–movement without a fixed destination.

This makes perfect sense for retail. It makes far less sense for almost anything else.

Offices require consistent daylight and efficient circulation. Housing demands access to windows, plumbing, and privacy. Even educational or medical uses must contend with the mall’s immense interior depths. To convert a mall is not simply to replace its tenants. It ‘s to renegotiate its relationship with light, air, and movement.

None of these challenges are insurmountable. But they make reuse expansive, uncertain, and slow–qualities that discourage all but the most determined developers.

The More Common Outcome: Subtraction

For many malls, reuse does not mean transformation so much as reduction.

Near Los Angeles, the former Whittwood Mall was stripped of its enclosed concourses and rebuilt as the open-air Whittwood Town Center. What remains is technically successful: the anchor stores survive, and new retail fills the perimeter. But the experience of the place has fundamentally changed. Walking from one end of the site to the other now means crossing open parking lots rather than moving through interior, pedestrian-friendly space. What was once a continuous architectural environment has been reduced to a collection of isolated buildings.

Elsewhere, the outcome is more absolute. In Akron, Ohio, Rolling Acres Mall sat abandoned for years before being demolished entirely and replaced with an Amazon distribution center. The transition is telling. Both the mall and the warehouse are long, single-purpose structures, but the warehouse reflects a different economic system–one optimized for logistics rather than public life. In both cases, the original architecture did not evolve. It disappeared.

An Alternative Path: Reinvention from Within

Yet not all malls vanish. Some are quietly reinterpreted–not by large developers, but by the communities around them.

In San Antonio, Texas, the former Montgomery Ward anchor at Wonderland of the Americas found a second life as the Wonderland Mercado. What had once been a department store became a dense interior landscape of small, locally operated businesses: food vendors, clothing stalls, salons, and informal gathering spaces. The transformation required remarkably little architectural intervention. The structure, built to accommodate retail, provided equally cable of accommodating a different kind of commerce.

What changed was not the building, but the economic ecosystem inside it.

Unlike the traditional mall model, which depended on national chains and centralized management, the mercado operates through fragmentation and adaptability. Individual vendors occupy small footprints. The space evolves continuously.

In this case, reuse succeeds precisely because it did not attempt to impose a new identity on the structure. It allowed the building’s original spatial–interior circulation, shared enclosure, controlled climate–to support a different form of public life.

Architecture and Its Economic Afterlife

The enclosed shopping mall was one of the most refined architectural responses to consumer culture ever devised. It coordinated structure, circulation, climate, and commerce into a single, unified environment. But that unity came at a cost. The more precisely a building is tailored to a specific economic system, the harder it becomes to separate the architecture from the economy it was built to serve.

This is what makes projects like Horton Plaza so compelling, and so precarious. Their futures depend not only on architectural ingenuity, but on financing and the unpredictable timelines of urban change. Adaptive reuse, in this context, is less a single act of transformation than a prolonged negotiation between past and present.

In some cases, portions of malls survive while others disappear. New streets are cut through former atriums. Offices replaced department stores. Interior corridors are opened to the sky. The mall does not return as it was. Instead, it dissolves, gradually absorbed back into the city it once turned away from.

This process rarely produces the clean, immediate resolution promised by early renderings. More often, reuse unfolds unevenly, shaped as much by financial realities as by design intent.

What remains constant is the physical presence of the mall itself.

Long after the escalators stop and the storefronts go dark, the structure persists. Concrete floor plates, steel frames, and parking garages continue to occupy valuable land. They cannot simply be ignored. They must be either erased or reinterpreted.

This is the quiet afterlife of the American mall.

Not every mall will be saved. Some will be demolished, their materials hauled away and their footprints cleared. Others will linger in partial states of reuse, suspended between their former and future identities. A smaller number will successfully reinvent themselves, their architecture adapted to new purposes their designers never anticipated.

Horton Plaza remains somewhere in between.

Its facades still stand. Its future remains uncertain.

The mall was designed to be permanent. Its afterlife suggests otherwise.

What happens next will not be decided by architecture alone.

If you’d like to discover more about Horton Plaza Mall, check out our video on the history and design of the mall.

Leave a comment