When you think about it, the shopping mall is a surprisingly you building type–barely seventy years old. And in that short span of time, it reshaped how Americans shopped, gathered, and spent their everyday lives.

Today, many malls are struggling or gone entirely. But this is not the story of every mall. It is the story of one building–the one that set the pattern, shaped everything that followed, and revealed the tension at the heart of the suburban life from the very beginning.

This is the story of Southdale Center.

A New Kind of Place

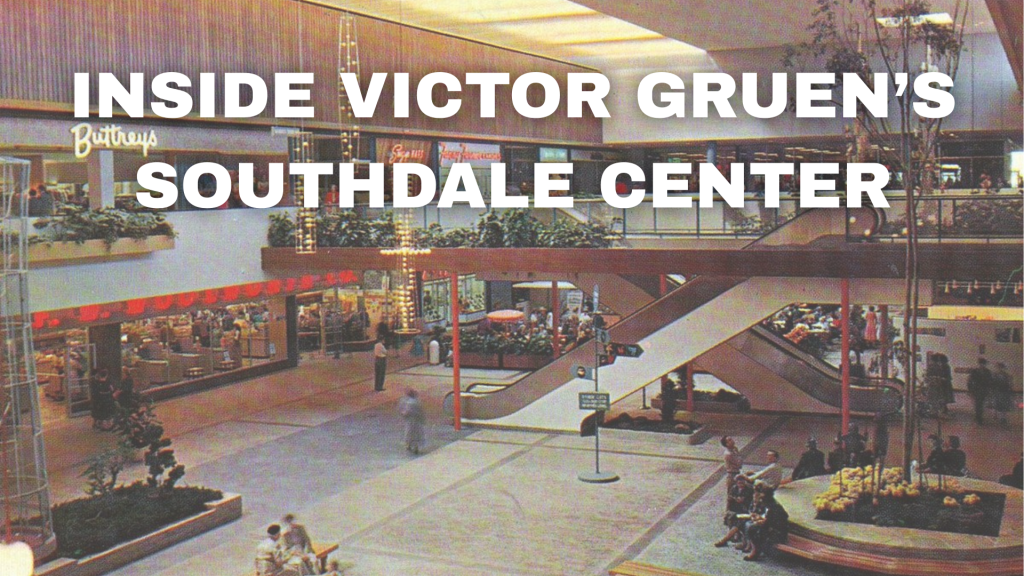

On a balmy October afternoon in 1956, more than 75,000 suburbanites poured through the glass doors of a brand-new, climate-controlled shopping center in Edina, Minnesota. Inside, the temperature hovered at a comfortable seventy-two degrees. Spread out beneath a single roof was over 800,000 square feet of retail–a completely new kind of suburban experience.

At the heart of it all was something no one expected to find in the suburbs.

It was called the Garden Court of Perpetual Spring, a massive interior space rising nearly fifty feet tall, scaled like a town square. It featured flowers, modern art, a sidewalk cafe, a reflecting pool, and the sound of exotic birds echoing through the air.

Standing on the second-floor balcony, looking down at the awestruck crowd below, was the architect who dreamed it all up: Victor Gruen.

For Gruen, this was simply an opening day. It was the culmination of more than a decade spent wrestling with a single question:

How do you create real public life in a country that keeps spreading itself thinner every year?

From Vienna to the American Suburbs

Gruen’s ideas did not begin in America. They began in Vienna, a city where streets served as spaces for civic life. Places to linger, to meet, and to simply exist together.

This world was in sharp contrast to what Gruen encountered when he arrived in the United States in the 1940s. Decentralization had begun before World War II, but after the war it accelerated dramatically. Downtowns hollowed out as cars carried people farther from the heart of town. In the process, civic life seemed to evaporate.

Gruen dedicated his career to finding a solution.

It began with essays and lectures, followed by increasingly radical proposals. In 1950, he designed a shopping center straddling a freeway in Houston. In 1952, he proposed a pedestrian-centered redesign of downtown Fort Worth. Each project pushed further against American norms and established Gruen as one of the most ambitious, and outspoken, thinkers in postwar architecture and planning.

The Birth of Southdale

That same year as the Fort Worth project, the Dayton Department Store, the same company that would later bring us Target, announced plans for a new kind of regional shopping destination. After nine months of research across the Minneapolis region, led by real estate analyst Larry Smith, the company selected a massive site in Edina, roughly seven miles from downtown Minneapolis.

What Gruen envisioned was far more than a shopping center.

He imagined a suburban civic core–a place where retail was only one component of a carefully planned community that included housing, offices, medical facilities, and public amenities.

For Gruen, this was an opportunity to demonstrate that architecture and planning could offer a cure for sprawl. For Dayton’s, it positioned the company as progressive and community-minded–a crucial argument in securing local approval to rezone more than four hundred acres of land for the project.

The master plan, unveiled in June 1952, encompassed 484 acres. Only 84 of those acres would be devoted to the shopping center itself. Beyond the sea of parking would rise a medical center, apartment buildings, offices, and eventually a new kind of suburban housing development.

Southdale Center would be the first phase.

An Indoor City

Given Minnesota’s harsh winters and hot summers, Gruen enclosed the shopping areas beneath a climate-controlled roof, made possible by recent advances in air conditioning. He even installed a heat-recovery system to improve efficiency.

But enclosure was not just about comfort. It allowed Gruen to design everything.

There would be no billboards

No traffic noise

No visual clutters.

The Garden Court–partially designed by Gruen’s chief architect, Rudi Bumfield–used clerestory windows to admit natural light without offering views outside. Its proportions echoed a Viennese plaza. Fountains, flowers, and modern art were meant to create a space where people would linger, socialize, and only then shop.

To keep both levels active, Gruen split the surrounding parking with a berm, allowing shoppers to enter on either the first or second floor–eliminating the idea that upper floors were secondary. Service trucks were pushed underground, hidden from view.

It was a complete architectural experience, and a proving ground on the possibilities for suburban communities.

Two Visions Under One Roof

Branching off the Garden Court were short concourses leading to two department stores. One was Dayton’s. The other belonged to a competitor, Donaldson’s.

Gruen insisted on two anchors to spread foot traffic and reduce financial risk. But Donaldson’s came with a condition, their store would be designed not by Gruen, but by their architect, John Graham Jr.

Graham had already shaped suburban retail with Northgate, outside Seattle in 1950, widely considered one of the first modern suburban shopping centers. His approach was direct, efficient, and unapologetically commercial.

When Graham saw Gruen’s plans for Southdale, he wasn’t impressed.

He viewed the vast Garden Court as wasted leasable space. He preferred long, narrow corridors where should could glance easily from storefront to storefront. He criticized the lack of exterior entrances to the anchor stores, the absence of signage, and the very idea that a shopping center should function as a civic hub.

To Graham, Gruen’s vision was not bold, just unrealistic.

Dayton’s sided with Gruen. But Graham was not wrong.

Even as Southdale was under construction, Dayton’s began selling off large portions of the surrounding land to outside developers. Tract housing soon replaced Gruen’s carefully planned community. The market moved faster than the master plan.

Success & Consequence

Southdale cost $20 million to build. When it opened in October 1956, work had begun on the medical center–but much of the broader vision had already slipped away.

Still, the response was overwhelming.

Journalists and architects traveled from across the country to see it. The Garden Court dominated the coverage. Gruen had created a working model for nearly all his ideas on curing sprawl. It would be up to the developers and cities of the country to implement them.

Critics remained, though. Frank Lloyd Wright famously dismissed Southdale as “all the evils of the town square and one of its charm.” But financially, the verdict was clear. Dayton’s sales jumped by roughly sixty percent in the mall’s first year.

Developers took notice.

Over the next two decades, Gruen would design more than fifty shopping centers across the country. But as the form spread, something essential was lost. The enclosure remained. The civic ambition did not.

What Remains

By the time Gruen fully realized what had happened, it was too late. His malls had become machines for consumption, not the centers of community he envisioned. He left his firm in the 1970s, returned to Vienna, and spent his later years criticizing the very buildings that made him famous.

Today, Southdale Center is almost recognizable from the place where Gruen once stood and smiled so optimistically. Poorly planned expansions and renovations stripped away much of what once defined it. The Garden Court is gone. The birds, fountains, and cafe replaced by kiosks.

One quiet remnant remains–Harry Bertoia’s Golden Trees–standing watch over what was once a suburban experiment.

And yet, even now, in the shell of Gruen’s grand experiment, people still gather. They talk. They linger. Proof that while the community Gruen envisioned never fully arrived, something of his vision still remains.

Southdale did not become the civic center Victor Gruen designed. It became the one people made.

Sources & Further Reading

This article draws on archival research, contemporary reporting, and architectural history. For readers interested in going deeper, the following sources provide additional context and detail.

- Alexandra Lange – Meet Me at the Fountain: An Inside History of the Mall (2022)

- M. Jeffrey Hardwick – Mall Maker: Victor Gruen, Architect of an American Dream (2004)

- Victor Gruen – The Heart of Our Cities (1964)

- Victor Gruen, Larry Smith – Shopping Town U.S.A. (1960)

Leave a comment