Architecture is often seen, at least by the broader public, as a lofty pursuit–something reserved for mahogany-lined parlors, dusty monographs, and university studios. But Frank Gehry refused to let it stay there. Through his work, architecture stepped out from behind the academic curtain and into the public imagination. He made it a spectacle, a conversation, and a cultural force.

Frank Gehry passed away today at the age of 96. His legacy will undoubtedly stand alongside the giants–Wright, Corbusier, Niemeyer–but more than anything, Gehry was the architect who made architecture cool. He made it approachable, emotional, and deeply human.

Nothing in Gehry’s early career gave any hints to his later work. He spent his formative years working for William Pereira and Victor Gruen, designing the pragmatic essentials of mid-century America: office buildings and shopping malls. But when he opened his own firm in the 1960s, something shifted. He found himself drawn not to the doctrines of modernism but to the eccentric voices of Southern California’s avant-garde art scene. In their work, he recognized an energy he wanted to translate into buildings.

Slowly, then suddenly, Gehry broke away. He experimented with unexpected materials and even more unexpected forms. His 1978 renovation of his Santa Monica home–an ordinary 1920s Dutch Colonial wrapped in corrugated metal, plywood, and chain-link fencing–became a manifesto. Part collage, part provocation, it announced the arrival of a new architectural language. The neighbors hated it; the world took notice.

By the 1980s, Gehry was ascending rapidly, buoyed by critics and champions like Philip Johnson. His experiments extend beyond architecture–cardboard furniture, fish-inspired sculptures, even early explorations into digital modeling. When he adopted CATIA, aerospace software designed for the aerospace industry, it liberated his imagination entirely. Technology finally caught up to his intuition.

The 1990s spelled the greatest burst of activity for Gehry. His work appeared everywhere–from Prague to Massachusetts to his adopted home of Los Angeles. And then came Bilbao. The Guggenheim Museum there was more than a building; it was a phenomenon. Technologically daring and culturally symbolic, it pushed the boundaries of what was possible. It came in on time and under budget, a fact Gehry often pointed out. Critics declared it the most important building of the late 20th century. Cities around the world would spend decades chasing its alchemy.

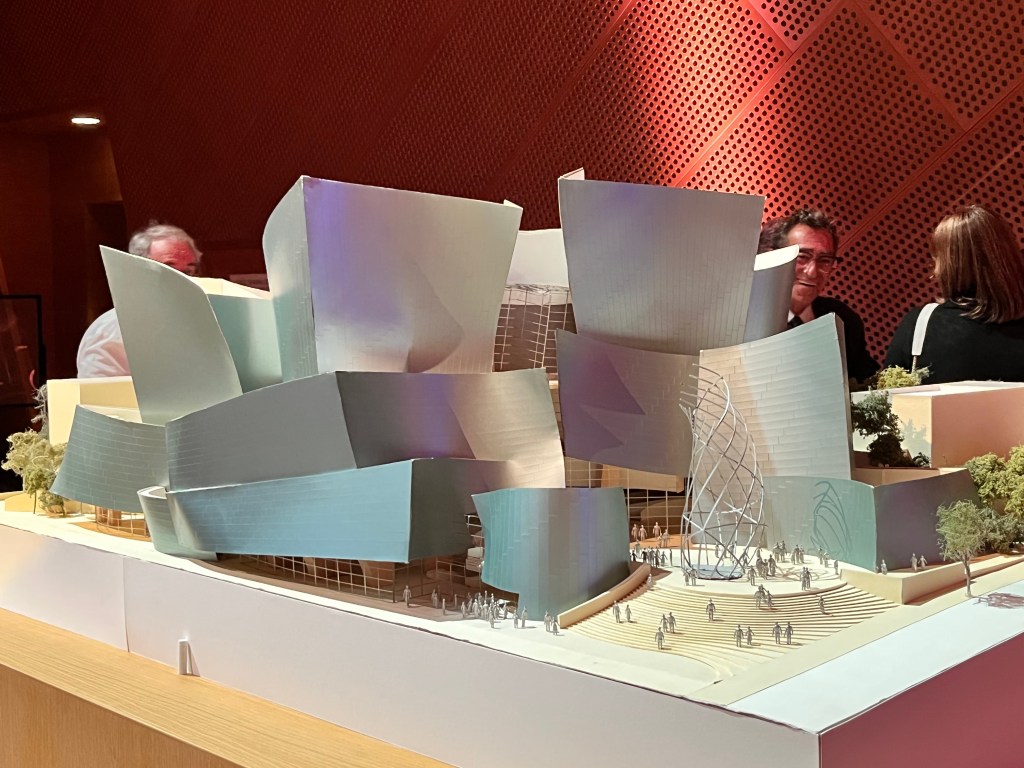

Back in Los Angeles, his fifteen-year odyssey to complete the Walt Disney Concert Hall finally bore fruit. When it opened in 2003, it gave the city something it had long been missing: a civic “living room,” a place that felt as uplifting as the music performing within it.

Even into his nineties, Gehry kept designing. He completed The Grand in downtown Los Angeles and shaped two major towers in Toronto. His energy seemed unshakable, his curiosity seemed endless.

Looking back at Gehry’s career, perhaps his greatest legacy is how deeply he embedded architecture into mainstream culture. He appeared on The Simpsons. he graced magazine covers. His name alone could sell luxury apartments–New York By Gehry–in a shaky real estate market.

For all the critiques that labeled his work as mere spectacle or cultural showmanship, Gehry’s buildings dismissed them effortlessly. His forms may have been flamboyant, but his priorities were profoundly human. Behind every sweeping curve and shimmering surface was a meticulously considered plan–and a belief that spaces should invite, comfort, and delight. His building may catch your eye, but they hold your attention because of their dedication to those who inhabit them.

We often hear that “they don’t build them like they used to.” Frank Gehry spent his life proving that wrong. He showed that architecture could still surprise, still challenge, still move us. And for generations to come, anyone who rounds the corner and catches sight of one of his creations will feel that familiar spark–an unexpected moment of wonder.

That is his legacy. And it’s a magnificent one.

Leave a comment