Few corporations have embraced architectural style as enthusiastically—or as visibly—as Disney. And in the 1980s and 1990s, Disney went all in on postmodernism.

At first glance, the pairing made perfect sense. Postmodernism was colorful, playful, and brimming with references to history and pop culture. Disney—the master of nostalgia and fantasy—wanted buildings that carried that same energy. So when Michael Eisner became CEO in 1984, he turned to postmodernism to reinvent the company’s physical spaces.

It began with a planned Marriott hotel at Walt Disney World. The deal was a kind of “thank you” to the Tishman Company, which had built EPCOT Center in 1982. But when Eisner saw Alan Lapidus’s design—a generic convention hotel—he was horrified. He reportedly called it a “refrigerator.” Trying to terminate the deal, Disney faced a lawsuit for billions. The two sides eventually renegotiated: Tishman would still develop the hotel, but Disney would have final approval on the design.

A design competition followed, attracting some of the era’s biggest names. The finalists were Michael Graves and Robert Venturi. Eisner couldn’t decide between them and suggested they collaborate—a pairing that never materialized. Ultimately, Graves won the commission for the vast Walt Disney World Swan and Dolphin Resort. For Graves, it was a chance to design at a monumental scale. For Disney, it was a declaration: the company was now a patron of architecture.

Eisner didn’t stop there. He brought together an eclectic roster of architects—Stanley Tigerman, Jon Jerde, Frank Gehry, Robert Venturi, and Robert A.M. Stern—to design everything from master plans for the new Euro Disney Resort to themed hotels, gas stations, and even an entire planned community called Celebration, Florida. Stern would even go on to serve on Disney’s board of directors.

This period was one of bold experimentation. At Disneyland Paris, guests could stay at Antoine Predock’s Hotel Santa Fe, an abstract evocation of the American Southwest, or at Graves’s Hotel New York, a glamorous Deco revival of Manhattan’s skyline. Gehry even designed an unbuilt “horizontal skyscraper” hotel for the resort. Not every project made it past the concept stage—Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown’s proposed Disney’s Vegas Hotel in Florida would have featured a neon-lit Mickey Mouse façade inspired by the Stardust Casino—but the ambition was unmistakable.

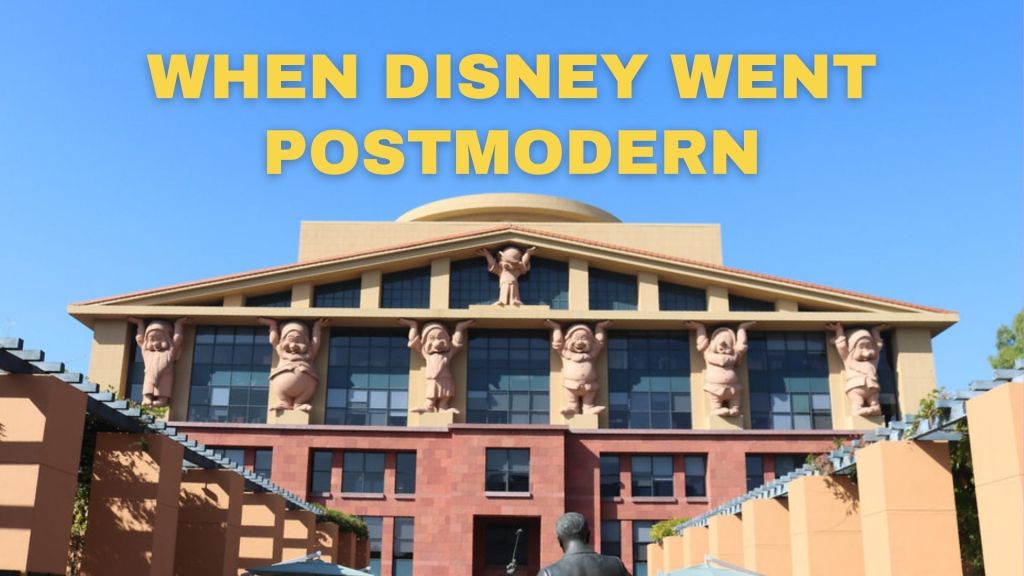

Perhaps the most famous, or infamous, of these projects was Michael Graves’s Michael D. Eisner Building at Disney’s Burbank headquarters. The original design was fairly restrained—an elegant office block with a pediment—but Eisner pushed Graves to make it more “Disney.” The result was a pediment supported by the Seven Dwarfs themselves, massive caryatid figures holding up the roof. It was tongue-in-cheek, theatrical, and unmistakably Disney.

Guests loved these buildings. They were immersive and imaginative, transporting visitors to another place and time. Stern’s Boardwalk Inn Resort at Walt Disney World was praised for its faithful recreation of turn-of-the-century Atlantic City, while Graves’s Hotel New York in Paris won fans for its grandeur and playful Art Deco flair.

Critics, however, were less kind. Ada Louise Huxtable dismissed Disney’s postmodern ventures as “pastiche.” What Eisner saw as prestige, many academics viewed as proof that postmodern architecture was frivolous—no more serious than animation or theme parks themselves.

Even within Disney, not everyone approved. Traditionally, all of Disney’s architecture had been handled by its in-house Imagineering division. Under Eisner, much of that responsibility shifted to the Buena Vista Development Company, which hired outside architects and wrote the design programs. The change created friction between Imagineers and corporate leadership.

When Eisner left in 2005, so too did his architectural ambitions. Disney’s retreat from high-concept design mirrored the wider rejection of postmodernism as a style. The company turned its focus toward immersive environments built around familiar characters and stories. Many of its postmodern landmarks were remodeled: the Swan and Dolphin lost Graves’s murals and elaborate lobbies, their interiors now resembling any other convention hotel.

Still, that era remains one of the most fascinating chapters in Disney’s design history—a time when Disney and postmodernism spoke the same language. Together, they proved that architecture could be theatrical, narrative, and just a little bit magical.

Leave a comment