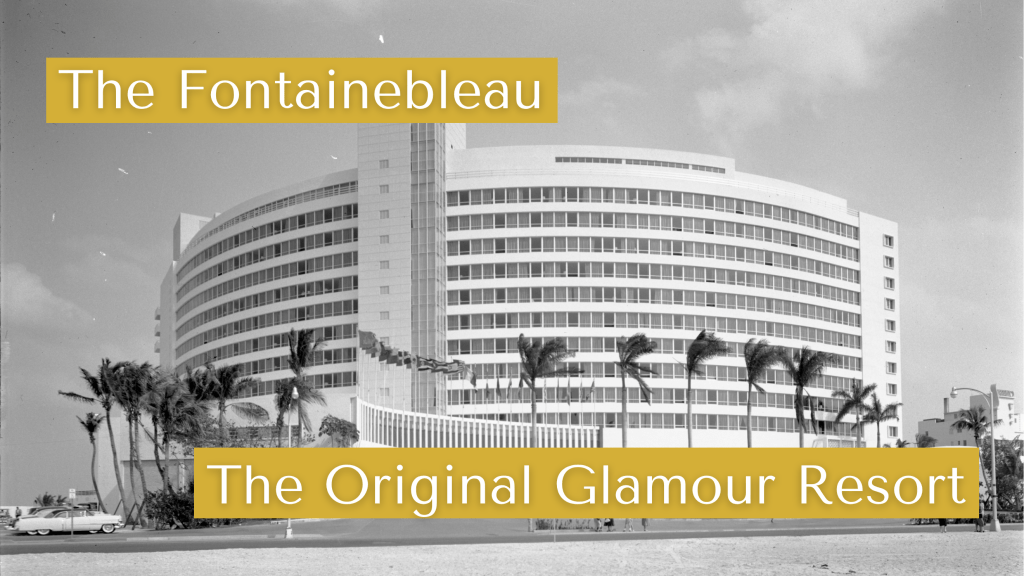

On the sun-drenched shores of Miami Beach stands a hotel that once challenged everything we thought a hotel could be. A glamorous resort, born of theatrical vision and architectural audacity, the Fontainebleau Miami Beach is one of America’s most iconic examples of mid-century modern design. Its creation sparked controversy, admiration, and ultimately, a legacy that endures some seventy years later.

A Bold Vision From Morris Lapidus

In 1952, the architect Morris Lapidus sat across from hotelier Ben Novack with a question: What does luxury look like?

Novack had purchased a parcel of land on Collins Avenue known as the Firestone Estate–right on Millionaire’s Row. Originally, Lapidus was asked to design only the interiors. But with characteristic confidence, he convinced Novack to let him design the entire hotel. He also agreed to a pay cut just for the opportunity. The commission would become the defining project of Lapidus’ career.

The name Fontainebleau–chosen by Novack’s wife during a trip to France–evoked elegance, European sophistication, and modern fantasy. That blend of tradition and spectacle would become the hotel’s design mantra.

From Stage Sets to Seaside

Lapidus began his career designing department stores and stage sets in New York, which trained him in visual drama and theatrical narrative. Though educated in the Beaux-Arts tradition, he gravitated toward modernist influences like Erich Mendelsohn. His genius lay in fusing old and new–combining classical motifs with curving modern forms.

For inspiration, Lapidus turned to the movies–especially the kaleidoscopic fantasies of Busby Berkeley musicals. He envisioned a hotel as an immersive stage, where every guest played the star.

Breaking the Mold in Miami Beach

At a time when Miami hotels were often boxy, utilitarian buildings, Lapidus introduced a curvaceous, 565-room tower inspired by Mendelsohn’s Schocken Department Store. The building’s sinus lines and ribbon windows gave it a sensual presence that captivated passersby on Collins Avenue. It was so distinctive that Lapidus argued the hotel wouldn’t even need a sign–and he was right.

Guests arrived under a grand porte-cochére and stepped into a dazzling lobby–a room designed for people to see and be seen. The interior juxtaposed modern elements with French baroque flourishes: sculptures, a mural of Rome’s forum, fluted columns, and a bowtie motif in the marble floor.

On one side of lobby was the so-called “staircase to nowhere,” and opulent, curving stair that led to a simple cloakroom but functioned primarily as a stage for glamorous entrances.

A Playground for Celebrities–and the Critics

The Fontainebleau quickly became a magnet for celebrities when it opened in 1954. Frank Sinatra, Jerry Lewis, and Liberace were regulars. Nightclubs like Club Gigi became hotspots for live entertainment. The pool deck, with its 265 cabanas and Versailles-inspired gardens, offered a fantasy lifestyle previously reserved for movie stairs.

Yet the architecture world was not impressed.

Critics denounced the hotel’s eclecticism as architectural heresy. Interior magazine went so far as to call it a “bastardization of architectural styles” in 1955, accusing Lapidus of failing both the profession and the public. Ada Louise Huxtable and other prominent voices ridiculed the Fontainebleau as “camp.”

But Lapidus was undeterred. He had long been dismissed for designing “fanciful” stories, and he had learned to embrace the criticism. He didn’t design for architecture–he designed for people.

The Spite Wall and a Growing Legacy

In 1959, Lapidus returned to expand the Fontainebleau with a new wing: The Versailles Tower. Though less dramatic than the original, it carried the same ribbon windows. Notably, the tower’s placement cast a shadow over the pool of the neighboring Eden Roc Hotel, designed–ironically– by Lapidus himself for Novack’s rival, Harry Mufson. The media dubbed the hotel’s blank wall as the “Spite Wall.”

Lapidus reportedly disliked the addition, but followed the client’s wishes. He added whimsical details like champagne bubble windows to soften its blunt form.

Despite the industry’s cold shoulder, Lapidus’ work began to attract the attention of emerging postmodern architects like Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown. They dubbed his style “Neo-Eclectic.” Lapidus’ work would soon be seen as a precursor to the postmodernist movement–a bridge between modernism and vernacular delight.

Even Philip Johnson, the high priest, at the time, of modernism, acknowledged Lapidus’ conviction:

“He is apparently so convinced that people want that sort of thing–that he’s willing to fight for it.”

From Miami to Las Vegas

Lapidus’ vision didn’t just transform Miami. It inspired a new kind of resort architecture across the country. Las Vegas developer Jay Sarno visited the Fontainebleau and decided to bring its flair to the Las Vegas Strip, opening Caesars Palace in 1966. The Fontainebleau model–opulence and fantasy–became the blueprint for American resort design for decades to come.

By the 1970s, the Fontainebleau had become both a cultural institution and a cinematic backdrop. It appeared in films like The Bellboy and Goldfinger, cementing its place in pop culture.

Reappraisal and Preservation

In time, the architecture community began to reevaluate Morris Lapidus’ work. No longer seen as tacky, his “Hollywood Baroque” became recognized as a meaningful response to modernism’s sterility.

When Lapidus passed away in 2001 at the age of 98, he was celebrated as the man who brought modernism to the masses and gave Miami Beach its architectural identity.

The Fontainebleau itself underwent a major renovation in 2002, with architect John Nichols preserving the original lobby while adding two new towers–carefully sited to respect the dominance of the original curved tower. The renovation removed the old pool deck and cabanas, but paid homage to Lapidus’ flair with updated design motifs.

In 2008, the Fontainebleau was added to the National Register of Historic Places, officially recognizing its architectural and cultural significance.

A Legacy Reborn in Vegas

In 2023, the Fontainebleau name was revived in Las Vegas with the opening of a long-anticipated sister property. The new resort paid subtle tribute to its Miami predecessor with bowtie patterns and fluted columns–but traded traditional opulence for contemporary art and minimalism.

Though the new building bears the name, it is the Miami Beach original that continues to define the brand’s identity and global recognition.

From Camp to Classic

The Fontainebleau Miami Beach stands today not just as a hotel, but as a cultural landmark–an embodiment of ambition, spectacle, and unashamed theatricality. It challenged the rigidity of modernism and elevated the resort experience to an art form.

What was once labeled “vulgar” is now hailed as visionary. And Morris Lapidus, long scorned by his peers, is now remembered as a pioneer who dared to make architecture joyful, democratic, and unforgettable.

Whether you’re an architecture lover or a curious traveler, the Fontainebleau is a reminder that buildings can do more than shelter–they can dazzle, provoke, and inspire.

Leave a comment